Viennale 2022: The Fires of Cinema

The Viennale is one of the last big film festivals of the year, to which I return every time as if I were a pilgrim. Perhaps because my cinephile (and, to a large extent, even personal) life is divided into a before and after. Maybe because it’s a festival with a unique artistic vision. Maybe because it is – of the big festivals – one of those that most respects the twin institutions of film criticism and curatorship, not just in terms of its guests, but also in terms of its contributions to the fields. Perhaps because this is the place where, year after year, the greatest filmmakers of the moment converge, finally freed from the hectic schedule of their premiere cycles, freed from the pressure of the emergent discourse about their work, who are joined by critics, scholars, historians and, in general, by those who think about cinema. It’s a royale of cinema, which is now in its sixtieth year; to mark its six decades of existence, the festival’s approach – devoid of the usual grandiloquent grandstanding seen in other places – has two main components: first, it invited six towering filmmakers (Claire Denis, Nina Menkes, Narcissa Hirsch, Albert Serra, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, and Serghei Loznitsa) to make a trailer for the festival, thus adding them to an illustrious gallery of filmmakers who have shot the Viennale’s trailers over the years (David Lynch, Manoel de Oliveira, Chris Marker, Lucrecia Martel, Lav Diaz, Tsai Ming-Liang — in the last 10 years alone!). Then, it also released a comprehensive, self-reflexive anthology: “On Film Festivals.“, featuring interviews, dialogues, and essays (critical or autobiographical) on film curatorship within festivals.

Four years after taking over the festival’s artistic directorship, Italian-born curator Eva Sangiorgi seems to have broken away from the long shadow of the late, legendary Hans Hurch, who ran the festival for almost three decades – the Viennale is now fully in her era, characterized by strong internationalism (featuring films from Eastern Europe and Central/South-East Asia, and especially Latin American) and much closer collaboration with the Viennese institutional framework, most notably, the Filmmuseum / Austrian Film Archive, a major partner of the event and central collaborator in the Austrian documentary film retrospective and the auteur retrospective dedicated to the Japanese filmmaker Yoshida Kiju (also known as Yoshihide Yoshida). Unburdened by the weight of competition, the Viennale truly feels like a festival of cinema, a place its film selection coexists democratically: in what regards both the lack of usual hierarchies imposed by awards, the fiction/documentary dichotomy (dismantled by Sangiorgi ever since her first edition as an artistic director, in 2018) and the distinction between recent films and heritage cinema. On top of it all, there is the beauty and elegance of Viennese cinemas (among them, the impressive Gartenbaukino, the refined Metro Kino, and the newly-restored Stadtkino), which adds even more to this atmosphere of absolute respect for the cinematic artform. In short, it’s a festival that you simply cannot miss.

At this year’s edition, I took the liberty – more than ever – of watching the Viennale’s retrospectives, which were divided into monography (three in number, dedicated to filmmakers Ebrahim Golestan, Med Hondo, and Elaine May), historiography (of Argentine film noir from the Peronist period) and the Yoshida Kiju and Austrian documentary retrospectives. On top of seeing a little bit of all of these, I also went to the special screening organized in memory of Jean-Luc Godard, which showed Film Socialisme (2010) – yet another choice that profoundly reveals the curiosity-driven and intellectually nonconformist ethos of Sangiorgi’s curatorial team: this is one of the filmmaker’s most divisive late films, certainly one of his most opaque (a film marking an aesthetic transitional between his two final creative periods, lying somewhere between Eloge de l’Amour and Le livre d’Image), combining genre elements (spy-film, family drama) with linguistic and cinematic experimentation and how strange and exciting it is to see a 35mm print of his scenes shot on crummy 2000s mobile phones, at loud parties, with its heavily distorted digital soundtrack modulated by the analogical medium.

The delight of the Viennale retrospectives lies not only in the mere presentation of these hidden gems – oftentimes restorations made at the prestigious Cineteca di Bologna – but also in the fact that they are always given detailed presentations by various professors, cinema scholars, and critics. This year alone, among those introducing the films in the monographs, one could discover Haden Guest, director of the Harvard Film Archive, Ehsan Khoshbakht, co-director of the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival (who spoke about attending the 100th – ! – birthday of Ebrahim Golestan), Aboubakar Sanogo, an expert on African cinema and professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, as well as Roger Koza, one of Latin America’s best-known film critics and curators (who made a superb introduction of Apenas un delincuente, 1949, where he said that the film anticipates, prophesizes the rise of one Diego Maradona, hinting at his legendary Mano de Dios). What a joy to find discover Elaine May here – whose The Heartbreak Kid has just recently been rescued from oblivion – with her wonderful screwball comedy, A New Leaf: even though its ending was confiscated and hijacked by its Hollywood producers, who imposed an obligatory happy ending, May proved herself as a worthy successor to Howard Hawkes well ahead of her generational colleague Peter Bogdanovich, while also performing the role of a naive botanist whose hand is taken in marriage by a spoiled heir who has squandered his fortune away (Walther Matthau, in fine shape).

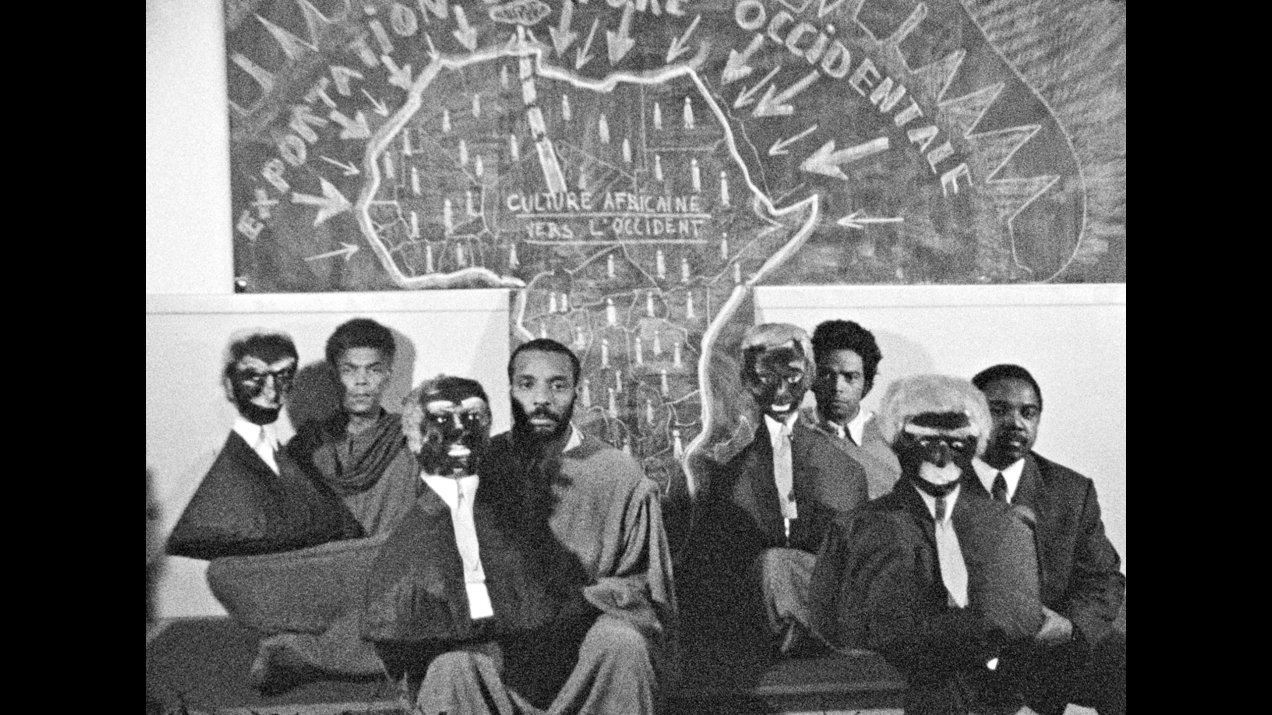

The retrospective dedicated to Med Hondo – one of the greatest African filmmakers of the 20th century – opened with an unusual double bill, which captured the director’s two sides: Mes Voisins (1971), a documentary with strong political overtones about the extremely precarious housing situation of African workers in post-war Paris, and Lumiere Noire (1993), an eclectic and comical mix of genres (thriller, noir, road movie) encapsulating a strong anti-authoritarian message, directed against the abuses of law enforcement, but also against the geopolitical octopus that still has its tentacles spread all over Africa in the post-colonial world. Of course, the focal point of the retrospective is the magnificent Soleil Ô (1969), shot by Hondo with his own pocket money over four years, a parable about the condition of the African migrant that is thrown into a world that has been ripped away his ancestral past and culture, ensnaring him into various forms of slavery, artificial conflicts, a subject to racism and discrimination. An incredible collage of political dialectics, moments of social realism, and metaphorical sequences – see the splendidly subversive scene of the Christianisation of Africans, or the one in which portraits of Malcolm X and Che Guevara burn, a sign of the absolute desperation of a revolution nipped in the bud; Soleil Ô is the kind of film where you feel that even the mere act of seeing it is a political, an affront to authority, an act of revolt.

By contrast, Ebrahim Golestan’s monography (complemented by Mithra Farahani’s A Vendredi, Robinson, presented at the Berlinale in February – which features his correspondence with Jean-Luc Godard) brings together both feature-length and short films, not only directed by the great Iranian auteur but also filmed or produced by him: and its first programme, Fires of Forough, is also the most fruitful, most daring from a curatorial point of view. It’s a collection conceived both as an homage to the great modernist poet Forough Farrokhzad, Golestan’s creative and intimate partner, and also as an ingenious progression: beginning with a bland documentary about an oil well fire, Fire-Fight at Ahwaz (1958), which could almost be an obscure Romanian Sahia studio documentary (missing only the discourse on the construction socialism), filmed in part by Golestan. Outraged by the film’s poor quality, he took back rushes and re-edited it with Farrokhzad in the infinitely superior Fire (1961); then follows a subversive short, Courtship (1961), part of an omnibus on love rituals from around the world made for Canadian television, which subtly parodies the custom of arranged marriages. And finally, The House is Black (1962), directed by Farrokhzad and produced by Golestan – introduced by Ehsan Khoshbakht as “the best film in history”: confronted with this sublime masterpiece, where Farrokhzad’s poems, an existential cry of despair, are combined with images from a colony of lepers (and so few other ways of suffering are more atrocious), I can only agree with him.

Of course, I couldn’t avoid the recent films shown at the festival – the Viennale is par excellence the festival where you can catch up with the year’s most circulated, opening with a screening of Tizza Covi and Rainer Frimmel’s new film, Vera, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival. A semi-fictional portrait of the eponymous protagonist, who is the daughter of Giuliano Gemma, a star of the spaghetti western genre. We see how the heroine loses herself, but also becomes complacent in the shadow of her much more famous father – perhaps the best scene in the film is the one where she visits the grave of the son of J.W. Goethe together with Asia Argento, discussing their status as daughters of famous men – while navigating a socially bipolar Rome, torn between unimaginable wealth and grim poverty. Where the docu-fictional side excels – its glimpse inside the life of the Gemma family and contemporary Italian industry, the scenes where Vera discusses shaping her persona after drag queens and when she discreetly reveals her cinephilia -, the completely fictional one ultimately fails. In a Rosseliniesque twist, the protagonist begins caring for an extremely impoverished family on the outskirts of Rome, doing so to the point of confusion and subterfuge, even though there are signals that something is rotten at the heart of it; and the rot wins out in the end, in an overwhelmingly cynical finale – in a contrast too stark to the heroine’s humanism.

A few other films shown this year on the Lido (along with titles from the Berlinale, Cannes, Locarno or Visions du Reel, amongst other festivals) have made their way to Vienna, so I took the chance to see a couple of them – The Listener, a subtle Kammerspiel directed by cult-actor Steve Buscemi, about a young woman working at a suicide hotline, or Alice Diop’s superb Saint-Omer, which, beneath its narrative, functions as a fascinating exploration of the concept of epistemology, posing the central question of realist cinema since the release of Aurora (2010): “what can we really know?”. Among them, there was also the Golden Lion-winning All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, by documentary filmmaker and journalist Laura Poitras, another portrait film, this time about legendary photographer Nan Goldin. The film is split into two temporal planes: the present, in which the artist forms an activist group working against the Sackler family (the owners of Purdue Pharma, which disastrously marketed the highly-addictive Oxycontin), and the past, which traces her biography through the photographs she took over the decades. It’s a film that fascinates through its subject rather than its form, which is formally stuck in the usual American documentary clichés – talking heads, lengthy intertitles, hand-held raw footage shot at the site of protests – with one small exception: certain biographical passages of the film are constructed as to mirror Goldin’s mythical eighties slideshow, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – in what is certainly the film’s forte.

It’s still early to draw the line over this sixtieth edition of the festival – which continues through Tuesday, November 1 – but one thing is already certain: you’ll definitely be seeing me here again next year.

The 60th edition of the Viennale runs between the 20th of October and the 1st of November 2022. The main image – which represents this edition’s graphic identity – was created by Rainer Dempf.

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.