Cinéma La Clef. A pocket guide to cinematic insubordination | The State of Cinema

«Ce qui me console, de toutes façons, c’est de savoir qu’il y a toujours quelque part dans le monde, à n’importe quelle heure, quand ça s’arrête à Tokio ça recommence à New-York, à Moscou, à Paris, à Caracas; il y a toujours, dis-je, un petit bruit monotone mais intransigeant dans sa monotonie, et ce bruit, c’est celui d’un projecteur en train de projeter un film. Notre devoir est que ce bruit ne s’arrête jamais. » – Jean-Luc Godard, in a letter to Henri Langlois, a text reproduced on the walls of cinema La Clef

A few months ago, I wrote about “La Loupe”, the passeur cinephile group (which has been meanwhile closed down by Facebook and has reopened, albeit under a tamer version), and ever since, my interest towards cinephile communities of resistance has been gaining constant momentum. At the same time, given the reopening of cinemas and the revival of the local festival circuit, I have kept on wondering about the issue of Romanian independent cinemas: we still have a very small number of such cinemas across the country while multiplexes have become the norm, initiatives such as “Save The Big Screen!” seem to have died off, and the situation is not at all pretty when it comes to the few screens that we still have – see the case of the Romanian Cinematheque, as documented by my colleague, or that of the Alhambra Garden. (And the few texts regarding local cinemas are, for the most part, still written in a romantic key – and they’re not even published by the local press, either.)

In this context, I discovered the spectacular story of how cinema La Clef (in translation, The Key) was saved – by a lively and ardent group of cinephiles who have taken upon themselves the task of saving the hall from closure by occupying it. Whether or not you agree with guerilla/political tactics, the case of La Clef is a truly fascinating one, as it reveals more than the particularities of the French legal system when it comes to cinemas, but also a situation in which the cinema community can involve itself in the salvation of a precious space that doesn’t work in the for-profit logic of the big multiplex chains, but is truly dedicated to arthouse cinema (be it recent or classical). As such, I constructed this article as a small explanatory guide, which expounds on a couple of key notions surrounding the case and its chronology – it may serve as a pocket guide to future cinematic dissidents, or as a story to rattle cinephiles out of their generalized apathy towards the fate of local cinemas.

What is an associative cinema?

By design, the associative cinemas in France exist in opposition to the private cinematic sector, which is based on competition – and belong to the same category as cine-clubs, film caravans or independent film education programs. As their name indicates, they are managed by associations which can also recruit volunteers, in various forms: direct management, endowment (public-private partnership), and renting. Their existence is indirectly owed to the legal framework of the French state’s intervention in cinematography, through the CNC (which offers funding both for production, as well as for distribution and exploitation, thus implying its financing of certain cinema halls), as well as the Regional Development Agency of Cinematography (ADRC).

A 2012 report of the “Opale” cultural resource and social/solidary economy center explains the history of associative cinemas, whose functioning is provisioned by the “Sueur” law of June 1992, which allows communities to involve themselves in the functioning of local cinemas (which also includes the act of investing). This report also estimates that around 20% of the cinemas in France at the time (!)[1] were functioning in this system and that this model was a direct contributor to the conservation of the cinema halls that were situated in the historical centers of French cities. They “answer to a social demand rather than to the laws of the market”, according to the authors, in a country that has special provisions for the so-called “art et essai” cinemas.

What was the initial history of the La Clef cinema?

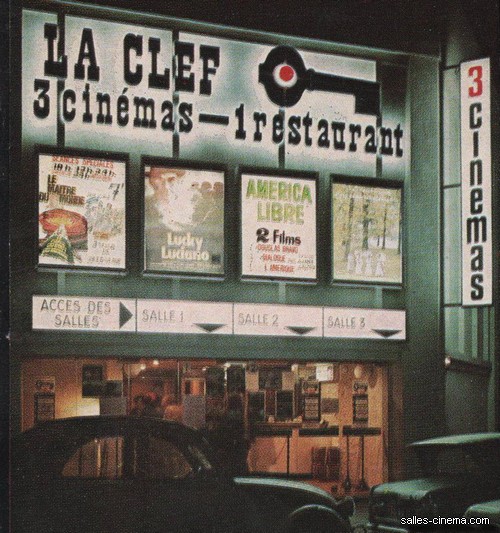

La Clef was originally inaugurated in 1973, in the chic and central Latin neighborhood of Paris’ 5th arrondissement, where the Sorbonne, the Pantheon, and the Jardin des Plantes are also situated. It functioned as an arthouse cinema from the very beginning, screening films directed by the auteurs behind the French New Wave. Initially led by a cinephile entrepreneur, the cinema entered bankruptcy at the beginning of the eighties, when a decision that would affect the space to this very day was to betaken: its building was put up for sale by its founder and was bought by a local chapter of the French cooperative bank Groupe Caisse d’Epargne.

Initially, the banking group didn’t operate any major modifications onto the building: they repurposed one of its three original screening rooms in order to set up a cultural center for its workers. The other two halls went to the Images d’ailleurs (Images from elsewhere) association, led by Tongoleze filmmaker Sanvi Panou, who took it over during (another) period of inactivity – and thus transforming La Clef into themost important Parisian movie theater dedicated to African and Arabic cinema throughout the nineties. Panou was motivated by the lackadaisical distribution of films directed by directors of color, which he kept in his cinema long after their normal distribution cycle had ended, and in the twenty years in which he led the cinema, he also organized a yearly festival.

The problems at La Clef began during his tenure: from one point onwards, the owners began to be bothered by the large crowds of people of color assembling there, says Panou, and so they started to neglect the cinema’s maintenance. The filmmaker led the cinema until 2009and starting with 2010, a new team, led by Raphaël Vion, Dounia Baba-Aissa, and Nicolas Tarchiani took over the hall, maintaining a similar curatorial line while shifting a stronger focus onto documentary cinema.

In 2015, the final blow arrives: Groupe Caisse d’Epargne announces its decision to sell the building hosting the cinema – and despite theprotests of the association that was managing it and of attempted crowdfunding, in April 2018, La Clef closed its doors, and the talks between the two parties failed. But only for a short period of time.

How was La Clef Revival born?

After closing down in 2018, the cinema lay closed for little over a year, until September 2019 – when a group of filmmakers and cinephiles going by the name of the Home Cinema Association (without implication on the part of the previous association) decided to illegally occupy the cinema and reopen it, with one clear goal in mind: to save Paris’ last associative cinema. Alongside organizing daily screenings in the evening, which could be attended free of charge, the collective also launched a multi-disciplinary cultural platform, which included a weekly fanzine, a podcast, creative workshops, and roundtables. Their terms to end the occupation? Getting a written declaration from the owners, in the presence of the press and of legal witnesses, that the hall on Rue Daubenton will never change its designation as an independent and associative cinema

Home Cinema’s strategy of obtaining films in the context of an occupation that was initially unfinanced was as simple as it was efficient: they obtained films managed by independent filmmakers and distributors, who offered them their titles free of charge. And the selection of the titles themselves was composed of rare, experimental, or political films – a context that, at the same time, was prime for an eclectic artistic direction, unlike that of any other Parisian cinema. The names that rallied to the support of the cinema, in various capacities, are absolutely stunning: amongst them Jean-Luc Godard, Claire Denis, Catherine Breillat, Olivier Assayas, Claire Simon, Mati Diop, Luc Moullet, Michel Hazanavicius, Laurent Cantet, Nicole Brenez, and Yann Gonzalez, along with entities such as the Paris Town Hall (which, at one point, offered to buy the building that housed the cinema), the French Society of Filmmakers, the French associations of directors of photography and editors, the Cinéma du Réel festival, and Nova (Bruxelles) and Videodrome 2 (Marsilia) cinemas. (An attempt to buy the space by SOS Grouppe, a social entrepreneurship NGO led by Jean-Marc Bonello, a close ally of President Emmanuel Macron, was however contested by Home Cinema, and the battle wages on in the Parisian courts.)

Despitea legal decision that obligated the association to evacuate the space until the 19th of December 2019, the collective appealed the decision – and during the wait for their court date, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, a fact that, in context, proved to be a blessing in disguise, since it allowed for the continued occupation of the cinema.

How did La Clef Revival function during the pandemic?

It might be that no other space than La Clef – doubly-shut down, by the pandemic and its owners, or, as Jean-Michel Frodon noted in a piece for Slate FR, “a situation borne out of several stories, enclosed into each other like matryoshkas” – was more suited to continue functioning during the lockdown, in an unconventional fashion: by screening films on the cinema’s outer wall. Its formal reopening, after the first lockdown, took place on the 19th of March 2020, with a screening of George A. Romero’s Zombie (according to TimeOut Paris) – and the tally of its first year of functioning is highly impressive: over 300 screenings (considering the pandemic!), with over 100 guests in attendance and over 20,000 entrances (!), according to a statistic published by the collective.

The most important (and visible) event of La Clef Revival took place in October 2020 when, with the help of cinema theoretician Nicole Brenez, the cinema hosted a carte blanche programmed by none other than the legendary Jean-Luc Godard over the course of a week, featuring films directed by Orson Welles, Kenji Mizoguchi, Norman McLaren, and Chris Marker. Godard also dedicated the following words to the members of the Home Cinema collective:

„nounous avons perdus les

clés, mais, hell as, avons

gardé les serrures, alors

voilà sept maffiozos sous

le garrot: au bord mer bleue,

lune vague après pluie,

splendeur ambersons, blin-

kity blank, paquebot tenaci-

ty, hitler connais pas, fond de

l’air rouge.

(un déserteur de l’alphabet)”[2]

What’s next for La Clef? And what are the lessons that we can learn from its case?

La Clef Revival is still operating and is just about to celebrate the occupation’s 2ndanniversary, and a cursory look over its current programming reveals titles directed by filmmakers such as Chris Marker or Alan Clarke, althoughthe legal term for the building’s vacation has been surpassed. Meanwhile, a graphic novel documenting the history of the cinema and of its occupation has recently been published.

For the moment, the members of the Home Cinema association are in the process of collecting the over 4 million Euros needed to buy the building, and a first crowdfunding attempt, which is simultaneously dedicated to the elaborations of support programs for independent (or politically engaged) distribution and creation, has overpassed its initial goal of 100,000 Euros. Through the same call, the association also took the oath of never implementing a system of stocks to manage the cinema financially and to assure that it will always be led by non-profit organizations with a horizontal organizational structure – a fact that, the organizers claim, would save the space from being targeted by housing market speculations and would assure that it will always operate at low costs for the spectators (especially for those with a precarious social background) and artists in search of a space for creation.

Sources:

„Lettre de Jean-Luc Godard à ses amis de l’est”. Jean-Luc Godard for Le Mag Cinema, published in December 2014.

„La Clef, cinéma fermé qui projette des films sur le toit pendant le confinement”. By Jean-Michel Frodon, in Slate FR, 23rd of April, 2020.

„La Clef Revival – Tous les jours, séance à prix libre”. By Rémi Morvan, in Time Out Paris, 20th of May, 2021.

„Sanvi Alfred Panou: Le moral necessaire!”. By the Cases Rebelles collective, 9th of May, 2015.

„Une occupation pour sauver le dernier cinéma associatif de Paris”. By the Home Cinema collective, the La Clef Revival website, undated.

„Save cinema La Clef”. In Sabzian, 14th of November, 2020.

„LE CINEMA ASSOCIATIF. Création, consolidation, développement de l’activité et de l’emploi.” In Les Repères De L’avise, published by Opale, March 2012.

[1] Of course, the number of these halls seems to have dwindled over the past few years – the Salles-Cinema website records only a few such cinemas across France, most of them situated in provincial towns, but it’s highly likely that this list is not an exhaustive one.

[2] Translation: “We [n: orig. nounous, wordplay; the word simultaneously means “nannies”] have lost the / keys, but, unfortunately [n: helas written as “hell as”, wordplay with the word’s meaning in English] we / have kept the locks, so / here are seven mafiozos lying under / the tourniquet: by the bluest of seas / tales of the wave after the rain moon / magnificent ambersons, blin- / kity blank, s.s. tenaci- / ty, hitler never heard of him, the base / of the air is red. / (a defector from the alphabet)”

Film critic & journalist. Collaborates with local and international outlets, programs a short film festival - BIEFF, does occasional moderating gigs and is working on a PhD thesis about home movies. At Films in Frame, she writes the monthly editorial - The State of Cinema and is the magazine's main festival reporter.