Watercooler Wednesdays: Welcome to Utmark, Halston, Crime of the Century

Watercooler Shows, the trending series that everyone talks about the next day at the office, around the water cooler… today there are no longer offices to go to, the movie theaters are functioning at limited capacity, and the content on the streaming platforms is increasing exponentially. Watercooler Wednesdays seeks to be a (critical) guide through the VoD maze: from masterpiece series to guilty pleasures, and from blockbusters that keep you on the edge of your couch to hidden gems; if it leads to binging, then it’s exactly what we’re looking for.

Welcome to Utmark (Dagur Kári, Kim Fupz Aakeson, 2021)

Twin Peaks, Fargo, Norwegian Western. Here are three marketing hooks – all true, by the way – that stand out to any cinephile who wants to do a bit of research before starting this Scandinavian series (Danish screenwriter, Norwegian cast, Icelandic director). The comparison with the two American series (which comes as positive in most reviews) would be flattering if Welcome to Utmark were just a sum of cinematic influences and elements pasted over that Scandinavian social-geographical background that we have all grown so familiar with and never disappoints visually (from black humor to violence to melancholic landscapes). The feeling you are left with after the 8 episodes spent in the Nordic North could very well be described as “a sum”, only there are so many valuable (and seemingly contradictory) elements that gather into this sum, that it’s practically a miracle that there is enough room for all of them, and on top of that, they all work almost perfectly.

Welcome to Utmark is, by all accounts, a neo-Western, but with a slight difference – here, the frontier is in the Wild North, and the deserts are replaced by stretches of snow. The characters are the very ones we know from the classic Western era: from the city schoolteacher who comes to bring “civilization” to the wild, to the corrupt and spineless local sheriff, to the ever-present and wealthy undertaker. The Fargo/Twin Peaks tone – which actually goes hand in hand with a long tradition of “otherness” in Scandinavian cinema – is visible in the peculiarities of these Western borrowed characters. The schoolteacher is a lesbian running away from a religious cult, the sheriff suffers from chronic diarrhea, and the undertaker invariably asks his clients: “with or without invoice?”. In the words of the local pimp – otherwise a very sensitive gentleman – quite unhappy with the provocative outfits of the new Albanian girls, whom he tries to dress up in his late wife’s clothes: “c’mon, a bit of style, we’re not making porn, we are in Norway, after all.”

The conflict that holds this whole gallery of characters and invites them to show their true nature comes, too, from the Western, and it’s a civilizational one. Finn, the white man (southern, the Norwegian invader), a sheep farmer, comes into conflict with Bilzi, a Sami reindeer herder. But unlike a classic Western, things happen the other way around here: all power and technology seem to be on the side of the native, not the white man. Bilzi watches his herds – indeed, far superior to his nemesis’ sheep – via satellite, Finn drives a piece of junk, and he, himself, is a piece of junk who won’t get going without a few (and Bilzi is the one who brings the firewater from the Finnish bootleggers). On a deeper level, Bilzi is the man of action (the character who does it all), Finn just wants to be left alone. Welcome to Utmark is a great example of this type of narrative dynamics, where the (anti)hero progresses and grows not thanks to his actions, but because things happen to him. Still, Finn does one thing, though: he runs over Horagallis, Bilzi’s dog that kept killing his sheep. It’s a ticking bomb that either goes faster or slower – Bilzi shoots another sheep, Finn shoots another reindeer – creating enough dramatic tension and allowing the show to freely explore all these characters in their comedic dimension.

That is because Welcome to Utmark is, by all accounts, a comedy. And the humor here is not intended to ease the dramatic tension (on the contrary, it shouldn’t disturb it), it runs parallel to the narrative, it even solves some of its puzzles. For example, the micro plot twist involving the border police officers who come to muddy the waters and the illegal Russian gin. While everyone involved in the smuggling (practically the whole town) keeps their head down, the feared border force – after all, two young officers with a taste for outdoor sex – quickly ends its mission following a hunting accident. On the other side, the hunters are obviously neophytes, searching for the famous wolf that haunts the outskirts of the city. The genius of the screenplay’s comedic ground, followed by the punchline later on in the series, deserves this little spoiler: the wolf does not exist, it’s all made up by the sheriff – an excellent sophist – to show Finn that his sheep are not killed by Bilzi’s dog.

Still, Welcome to Utmark is not a Western comedy. Humor is not intended for parody, and these characters – despite their design that makes them unique thanks to some funny quirk – are by no means caricatures. That’s because the show was wise enough to move the battle between “good” and “evil” inside – the cornerstone of the classic Western. Divorce, grief, alcoholism, self-hatred, domestic violence, sexual doubts, suicidal romantic devotions… demonic possession. Each of these characters “goes through something” and tries to maintain their moral compass. Each of them has a personal story to play, not just a supporting role in a comedy/genre film. And when it’s their turn, each character and their drama fill with an unexpected tenderness the same scene that just a few minutes ago was an excellent comedy… or a neo-Western… or a family drama where the main character is very much a child.

Welcome to Utmark is available on HBO Go.

Halston (Ryan Murphy, 2021)

“God bless Jackie Kennedy!” / “Fuck Jackie Kennedy!” Here are two lines that summarize about 7 years of American fashion designer Roy Halston’s life. The well-known pillbox hats worn by the first lady at the inauguration of John F. Kennedy in 1961 (but also the hat she was wearing when the president was assassinated, two years later) were his creations. According to this biographical series, Jackie made Halston famous by wearing his hats. Then she turned him into a fashion icon by giving up hats and forcing him to reinvent himself and make the transition from dressmaker to fashion designer – aviator uniforms, US Olympic team uniforms, perfumes, suitcases, carpets, and just about anything that could be branded with his name.

Halston is filled with such informative notes at the junction of fashion and history, pop culture and name-dropping (all with an excellent soundtrack, which spans the three decades of Halston’s dominance, from hippie to disco). But what caught my attention about the whole story with Jackie and the era she defines is that Halston’s (played by Ewan McGregor) two lines are separated only by the title card. Only 3 minutes in the first episode and two encouraging things, both confirmed later, resulted from here. First – a biography where such detail is a springboard to something else must be damn interesting. Second, which also has to do with the fact that the series has only 5 episodes (instead of the standard 8, which has almost become Netflix’s trademark): is it possible that this time Netflix has not made a pact with that devil of streaming who stretches a script until its dramatic weave wears out?

The answer to this question, however, is a bit more nuanced, because in reality there wasn’t much to drag out. Halston took over America with fancy fabrics (Ultrasuede, cashmere) and light, flowing one-piece designs, from which all unnecessary accessories were removed (caftans, dress-shirts). Halston is/was synonymous with the luxury you can lie around in and the liberating cut you can dance disco in. Halston, the series, seems to adapt to this principle and floats around for only 5 episodes like a colorful caftan, without being dragged down by too much drama. There are of course tense moments, panic attacks and emotional breakdowns, drug addiction, sexual addiction, and the HIV epidemic, all out of the shadow of an unhappy childhood.

Some critics lamented that Halston doesn’t dig deeper into the character’s psychology, that it prefers style over content. “Reviews don’t matter,” says Halston at crucial times of failure, when others don’t seem to understand his creative vision. It’s not that the film critics didn’t understand what Halston is about, the better question is: does it matter? Cinema, especially the “small screen” type, is also meant as a consumer product… just like fashion. Halston is actually interesting from this standpoint because he addresses pretty seriously the issue of the arrangements between art and industry (and it’s not so different compared to how things work in the film industry). With the help of investors who direct his talent according to market trends, Halston practically builds an empire by licensing his brand to no end: Halston perfumes, Halston carpets, Halston suitcases. When the empire begins to falter, it’s not because of cocaine and endless parties, but because Halston refuses to put his name on a pair of jeans in good time, and Calvin Klein saturates the market and takes all the profits.

“You’re only as good as the people you dress” was one of Halston’s mottos, and the show delivers by casting Ewan McGregor in the lead role. Halston is a fashionable show about fashion. It’s consumer cinema, hassle-free and excellently executed, but it’s McGregor’s performance that makes it memorable. McGregor lying on the couch, in Halston’s skin (and in Halston’s clothes, the inherent black turtleneck), speaking with Halston’s voice (a lingering posh accent, made up only for himself by a boy escaped from rural Indiana), is the reason it makes you lie on the couch, basically watching a fashion show with lines. Halston – alone or accompanied by his entourage of supermodels, The Halstonettes – entering Studio 54, getting out of the limousine, or simply parading all over NY in minimal chic combinations (red, black, white, but never all three at the same time), always accessorized with thick black glasses and a lighted cigarette in his hand… this is where the sex appeal of this Netflix miniseries seems to reside. “I want people to recognize my creations on the street and cry out: This is a Halston!” I had no idea who Halston was before I watched this show, apparently, those familiar with his life and work were pleased with the performance of the Scottish actor. But what I can definitely say about Halston is: This is a McGregor!

Halston is available on Netflix.

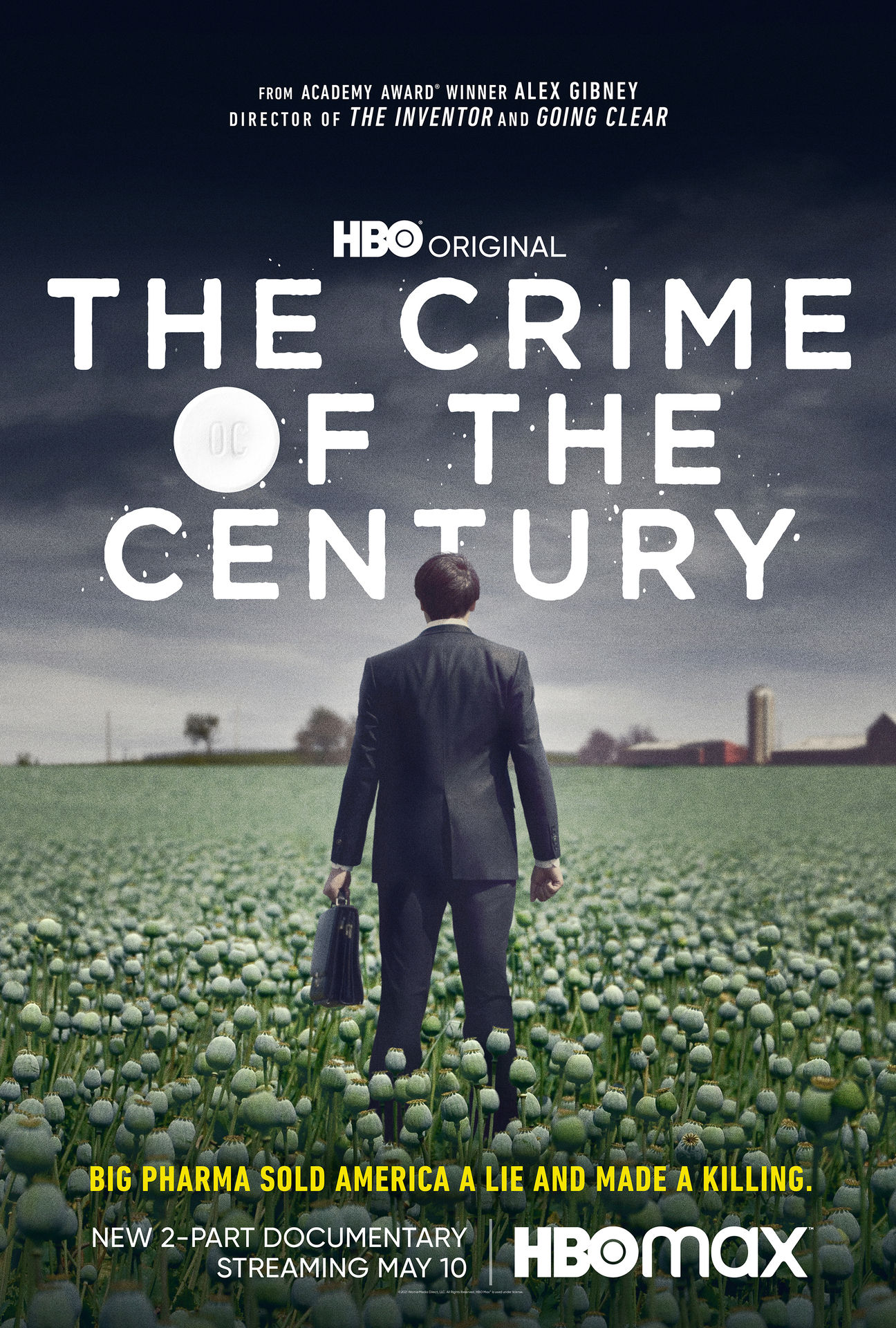

Crime of the Century (Alex Gibney, 2021)

In Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, there is a wonderful scene where the character played by Julianne Moore is waiting in a pharmacy to fill her dying husband’s prescription: Prozac, liquid morphine, and others. The old pharmacist and his assistant exchange sly glances, scanning her suspiciously, whispering, and making all sorts of calls to check the prescription. The assistant tries to get something out of her, to find out if she uses the medication as a drug, or at least to make sure she won’t use them all at once.

Crime of the Century, the HBO mini-miniseries (only two episodes) about the US opioid epidemic, reminded me of this scene. Impertinent, yes, but ultimately out of genuine concern for the patient, this pharmacist’s assistant could have very well saved some of the nearly 500,000 Americans who died from a synthetic opioid overdose. Doctors, pharmacists, pharmaceutical distributors, paid bureaucrats, sponsored politicians, are the weak links in a chain that starts with manufacturers and ends with patients/addicts. Crime of the Century deserves its name precisely because there are so many people at fault; the crisis of synthetic opioid use is practically the perfect storm, which could only happen in America.

But let’s start with the beginning, although we won’t go as back as Ancient Egypt as director Alex Gibney does in a huge effort to condense information. It’s an effort doubled by an innate talent for storytelling: talking heads, archive footage, animations, music, all these are combined flawlessly (let’s not forget that Gibney also won an Oscar for Documentary, Taxi to the Dark Side). Opium, morphine, codeine (natural), heroin, oxycodone, fentanyl (synthetic) – all were medicines at one time. The last two still are and have caused the worst public health crisis in the US between the HIV epidemic and COVID19. These medicines are also drugs – that is, used illegally and incorrectly. But the effects (addiction, overdose) are the same for all consumers: those who need them and take them on prescription, those who do not need them and take them on prescription, and those who simply buy them on the street. But the circle becomes even more vicious, since the tolerance gained over time (or the inability to buy prescription drugs) pushes consumers toward substitutes like heroin.

In this perfect storm, there is of course a turning point, and here the fingers invariably point to Big Pharma, and its innovations. Not so much the technological ones as those related to the business model: using advertising strategies (in the EU, for example, advertising prescription drugs has been illegal since 1992), sponsoring the doctors who prescribe their medicines (the famous American lobby), unlimited bonuses for sales agents (performance and profit culture). These substances existed long before 1996, when Purdue Pharma practically invented a need for a drug (OxyContin), and not the other way around. Opioids are very powerful analgesics used to treat acute pain (cancer, postoperative, etc.); the OxyContin innovation was to expand this niche to virtually any pain. To persuade doctors to prescribe as many of these very powerful drugs as possible, the manufacturer has initiated a revolution in medical practice. In addition to the four well-known vital signs (pulse rate, respiration rate, blood pressure, body temperature), OxyContin manufacturers pushed forward a 5th: pain (subjectively rated on a scale of 1 to 10).

Crime of the Century is a “tour de force” – information, emotion, and impeccable cinematic craft – that makes you better understand why medicines and drugs are translated into English by the same word. Alex Gibney’s documentary comes with this revelation in regards to the polysemantic value of the word drugs. In fact, the two meanings are identical, and what makes the difference is not the product, but three mutually weighting factors: whether the substance is legal, whether it harms you, and especially, who sells it to you. And depending on who sells it to you, the first two factors change their direction very easily.

The sensitive and comprehensive eye of the director glides over the bankrupt mining cities, embracing shadows of the American dream in melancholy. Each character, good or bad, is framed in his own biography: the billionaire pharma who started with the dream of eliminating pain, the discredited doctor and the Mormon widower who is still trying to forgive him, the narcotics agent who dreamed of being a police officer as a child, the paramedic who chose his profession because two of his colleagues collapsed in class after an overdose with Oxy. American values emerge at every step in this film: from work ethic (work hard, play hard and then treat all your conditions by trying the most hardcore methods possible) to entrepreneurial culture (a pharmaceutical company even created the fentanyl lollipop with lemon flavor). Besides the investigative part and presenting the information in a digestible form for any viewer, Crime of the Century stands out for its ability to poetically reflect an American tragedy.

Crime of the Century is available on HBO Go.

Film critic and journalist, UNATC graduate. Andrei Sendrea wrote for LiterNet, Gândul, FILM and Film Menu, and worked as an editor on the "Ca-n Filme" TV Show. In his free time, he works on his collection of movie stills, which he organizes into idiosyncratic categories. At Films in Frame, he writes the Watercooler Wednesdays column - the monthly top of TV shows/series.