The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner: On the “Mission: Impossible” Series

It’s 1996, Mission: Impossible has only been running for five minutes, and both Ion Caramitru and Marcel Iureș have already appeared on screen. Caramitru disappears right after the film’s opening scene. He plays some kind of Russian diplomat, the victim of a cruel setup by Tom Cruise’s team, which, using theatrical props (masks, fake walls, fake blood), tricks him into thinking he accidentally killed a prostitute. Caramitru cries and mumbles a few words in Russian. In the role of another Russian – one who gets hold of a floppy disk containing the list of all CIA agents in Eastern Europe – Iureș doesn’t utter a single word. He gracefully strolls through an embassy during a reception, tailed by Cruise’s crew. He manages to slip the floppy disk into a slot, steps out for a smoke in the bluish mist along the banks of the Vltava – and dies. The director is Brian De Palma, who is clearly flexing his stylistic muscles: he evokes Hitchcockian camera angles (like those used by Hitchcock in the reception scene from Notorious, where Ingrid Bergman hides the key stolen from the wine cellar in her palm), and the scene showing Cruise and Kristin Scott Thomas in a quiet exchange under the Prague night is styled in such a way (make-up, lighting, framing) that they could easily pass for the stars of a spy film Hitchcock might have made during World War II.

Cruise doesn’t really belong there – neither in World War II nor the Cold War. He seems out of place in a neo-expressionist depiction of a Central European capital; he doesn’t mesh with actors and actresses who have either a Nosferatu-like aura (Iureș) or that of a worldly woman (Scott Thomas). Cruise looks like an enthusiastic American kid – and at that time, despite Top Gun, he still wasn’t associated with action films and stunts. De Palma surrounds him with incredibly stylish English and French women – Scott Thomas, Vanessa Redgrave, Emmanuelle Béart – but gives them nothing interesting to do. Same for Jean Reno, for that matter.

By the mid-’90s, Hollywood had started adapting 1960s TV shows with James Bond–inspired plots for the big screen. There was The Saint (starring Val Kilmer) and The Avengers (with no relation to Marvel), but only Mission: Impossible was successful enough to launch sequels – seven over the next 30 years, the latest of which is just being released now. And its success wasn’t limited to the box office: it also won over the editors at Cahiers du cinéma, big fans of De Palma, who ranked it eighth in their top 10 for 1996. Premiering in 1966, at the peak of the 007 craze, the Mission: Impossible TV series stood out from other imitators thanks to its thrilling musical theme (by Lalo Schifrin), its focus on teamwork (coordination, synchronization, etc., like in heist movies), and those masks the good agents used to impersonate the evil ones. The 1996 film preserves all these elements, but what sets it apart is De Palma’s talent for crafting set pieces or pièces de résistance – cinematic passages that can stand apart from the rest of the film and be anthologised.

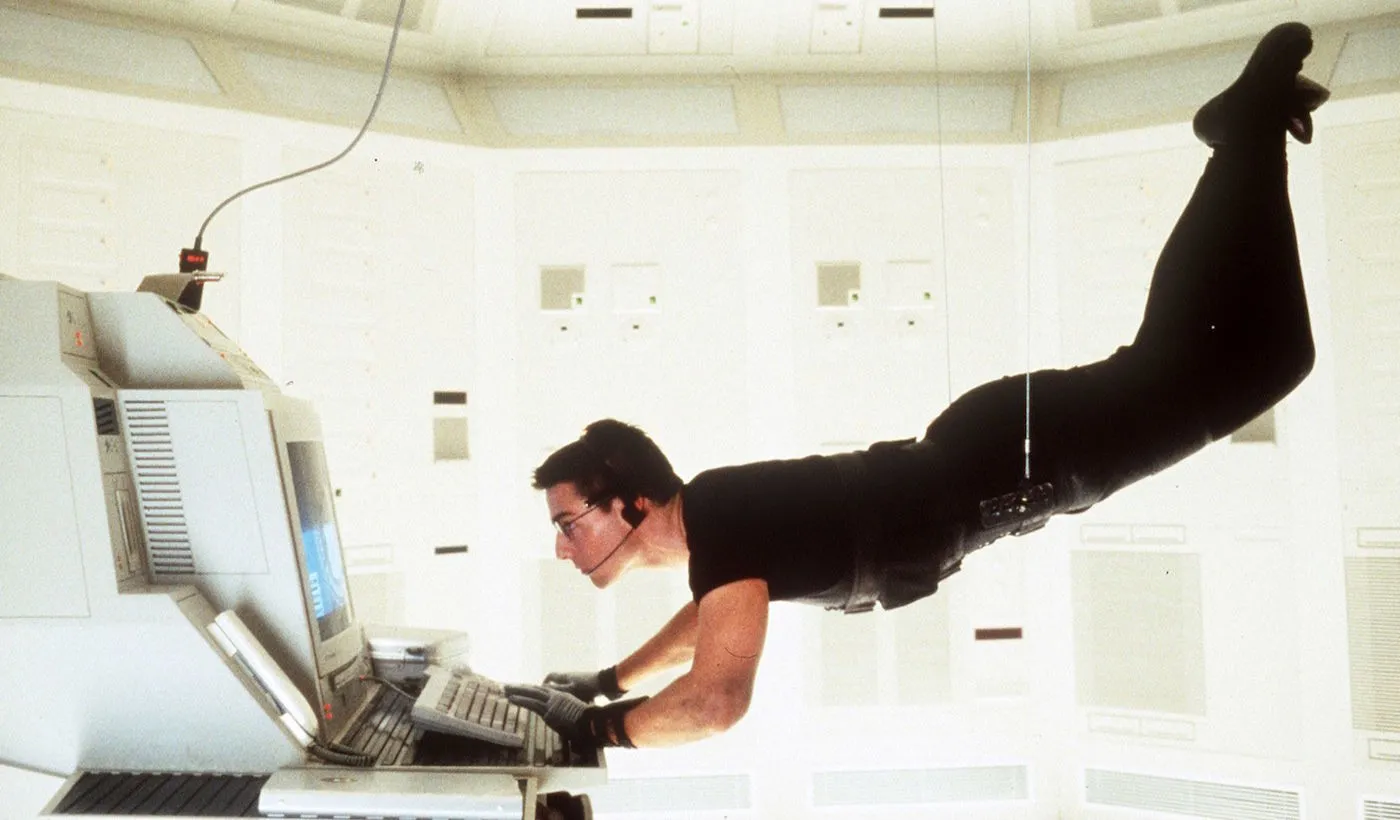

Though nicely choreographed, the Prague reception scene isn’t spectacular enough to qualify. But the acrobatic infiltration of Cruise into a restricted CIA headquarters room certainly is. Since not even a single strand of his hair can touch the ground, he descends from the ceiling like a spider. (Jean Reno puppeteers him.) De Palma orchestrates a series of amusing complications and brings it all to a climax with a minimalist special effect – a close-up shot of a gloved hand reaching out at the last moment to catch a drop of sweat that could trigger the alarm.

Cruise’s self-reinvention as an acrobat begins there, but it will take a few more entries before the series properly refocuses on his body – on how he pushes it to the limit. Mission: Impossible II (2000) opens with him climbing a mountain, but beyond that, the new director, John Woo, has other ideas. Like Brian De Palma, Woo was at that point a filmmaker with a strong stylistic signature, hired to fulfil a studio assignment and, as much as possible, to compensate for the essentially impersonal nature of such a gig by sprinkling in signature flourishes. Among Woo’s trademarks: a dove flapping through a ring of fire, and Tom Cruise growing his hair long so it can blow in slow motion. (Combined with Woo’s tendency to lay on postcard clichés and romantic-softcore tropes – beautiful women descending from yachts with scarves fluttering around their necks, cruelly grinning men waiting for them on the promenade, Spain equals flamenco, etc. – this effect turns entire sequences into shampoo commercials.)

The truth is, Woo is out of his element here: the shootouts he excels at staging don’t erupt until nearly an hour and a half into the film. Up until then, the plot revolves around a perversely erotic intrigue – although he falls in love with Thandie Newton, Cruise’s character pushes her into the arms of her ex-boyfriend, played by Dougray Scott, in order to locate the deadly virus he’s stolen. This love triangle emulates the one in Hitchcock’s Notorious (with Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains), just as the dynamic between Scott’s villain and his trusted henchman, played by Richard Roxburgh, tries to evoke the homoerotic chemistry between James Mason and Martin Landau in North by Northwest. But Woo lacks the subtlety these perversions require, and Cruise, with an affect like that of a replicant from Blade Runner, is rarely a convincing lover. In this second instalment, the Mission: Impossible series is still fumbling toward a formula – and seems to be losing its way.

It took a J.J. Abrams – not a Woo or a De Palma, but a non-stylist, a director without the reputation of a true auteur – to begin stabilising the formula. Mission: Impossible III (2006) is less pretentious than II, but slicker. The cities Ethan Hunt (Cruise) visits for break-ins are interesting (the Vatican, Shanghai) and filmed with less cliché than Woo’s Seville. The object of his break-ins is a cylinder referred to by everyone as the “Rabbit’s Foot”; like the virus in II or the agent list in I, the “Foot” belongs to the category of cinematic objects Hitchcock dubbed “MacGuffins” – things the characters would do anything to obtain, while the audience doesn’t really care what they actually are – but Mission: Impossible III is cool enough to take the idea to its limit: even Ethan himself doesn’t quite know what the “Rabbit’s Foot” is (probably another virus). Other fun plays on convention: part of the Shanghai heist isn’t shown to us (we’re made to wait in the car, in the company of Ethan’s team), but for the first time, we do get to see how one of those masks is made – the ones that allow an agent to perfectly impersonate an enemy operative (voice included).

J.J. Abrams makes progress on humanising Cruise, though it’s not easy. The superstar is now 44, maybe a year or two older than the “generic” James Bond. But he still looks much younger. He’s not interested in demonstrating any of the savoir-faire Bond displays in his dealings with bartenders, croupiers, or countesses. Ethan has no vices – he’s not even a hedonist. He’s a perfectionist and obsessive – perpetually consumed by the mission at hand. He never has time to spare, and he’s a fanatic anyway. Unlike Bond, he’s not an individualist but a team player (and the slogans he uses to talk about teamwork are distinctly American), though the way he talks to his teammates always makes it clear who’s in charge. Mission: Impossible III tries to increase his human factor by giving him a civilian wife (a nurse), played by Michelle Monaghan, and especially by placing both of them at the mercy of a villain who, being played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, feels far more capable of real cruelty than his predecessors.

What the film lacks are anthology-worthy set pieces – neither the Vatican infiltration nor the Shanghai one rivals the cinematic bravura of the 1996 Langley sequence. However, this is where Cruise – in Shanghai – starts seriously running. He runs over tiled rooftops, across terraces, over bridges, through bazaars, through labyrinths of alleys, through crowds, in front of cars, all while a teammate on the other side of the world gives him instructions over the phone: “Right! Left! Jump!” Ethan Hunt has found his iconic pose, his signature move.

Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (directed by Brad Bird, 2011) perfects the formula. Like Bond, Ethan will visit at least three countries per adventure. In the tradition inaugurated by the 1996 film, which began in Prague, some of them may be former Soviet spaces or places that still retain chic Cold War shadows (Berlin, Vienna). Also in the tradition of the first instalment, the enemy will ultimately be found at home, the final battle being one between structures of the American deep state. Following the Bond series model, references to real-world political or military conflicts will be avoided as much as possible. (When the Bond series deviated from this strategy – such as in 1987, when it had the protagonist ally with future Afghan Taliban against the invading Soviet army – the producers later came to regret it.) A sense of connection to current affairs (primarily technological ones) will go hand in hand with maximum abstraction, in the interest of escapist entertainment free from the headaches brought on by contact with the real world. Contributing to the abstraction is the restriction of human interest content, although Ethan and his friends will still occasionally experience guilt pangs and other synthetic emotional convulsions.

Over the course of an adventure, Ethan will carry out one or two infiltrations into inaccessible locations (the Vatican, the Kremlin). At some point, there will be a reception, a gala, a black-tie event (Maggie Q wears an incredibly sexy dress in Mission III) – a touch of Bond-style high life (even if the frustratingly chaste – or let’s say it outright: asexual – Ethan will remain aloof from such frivolities). These infiltrations will involve both team play and solo acrobatics. They will have a significant high-tech component, but the decisive factor will be that Ethan puts his body into play – and so does Cruise. Mission I showed Cruise descending like a spider on wires from a high ceiling, and Mission II showed him hanging by one hand from a cliff’s edge, over a chasm. But it’s Mission IV – which has Cruise climbing the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the tallest building in the world – that proclaims his rebirth as a stunt actor in the tradition of Burt Lancaster, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Jackie Chan, thus reasserting, with new authority, the spotlight on the phenomenon of his body. The authority also comes from the fact that this is a 49-year-old body – an age by which Lancaster, Belmondo, and Chan had already started slowing down; yet Cruise is just getting started. And biology isn’t the only current he swims against; there are also the currents of an era in which the movie star – as a unique, exceptional personality – is no longer what it used to be. Multiplexes are now dominated by Marvel-like constellations – constellations of characters (Captain America, Thor, etc.), not actors – and bodies that are CGI (i.e., animated), just like the buildings they crash into. It’s very interesting that Brad Bird, the director who aided Cruise in this reorientation, was himself a filmmaker specialised in animation (The Incredibles, Ratatouille).

Bird, however, seems to have taken Jackie Chan as a model when he added a dose of slapstick comedy to Cruise’s acrobatic and pugilistic exploits. The difference is noticeable from the first action scene – a mass escape, with fighting and all that, from a Russian prison: Cruise throws a punch, runs, pulls off a stunt, runs a bit more, with guys chasing him – it’s Jackie’s style. To go up and down the Burj Khalifa, Ethan uses special gloves meant to provide Spider-Man-like grip, but one of the gloves runs out of battery – the idea that gadgets can fail, both comically and catastrophically, becomes a running motif in this fourth installment, unlike in the previous ones (and unlike in Bond films), but it’s practically a law in Chan’s universe. When trying to get back down to the apartment he started the climb from (on the 123rd floor), Ethan finds that the rope is too short, so he has to make a deadly jump. “You don’t have enough rope,” his teammate Benji (Simon Pegg) shouts from the apartment, unsure how else to help. “No shit!” Cruise shouts back, irritated – and instantly becomes more likeable than he ever was under John Woo or J.J. Abrams, who strained so hard to give him a sentimental life in order to humanise him.

And then there’s his running. In Mission IV – Ghost Protocol, he exits the Burj Khalifa and starts chasing a villain, with a sandstorm on his heels: this is the moment when his run becomes iconic. (The next shot of him running is filmed from the darkening cloud’s point of view.) The chase continues in cars, and then again on foot. Cruise falls hard, keeps getting scraped by things – sure, not too badly, because it’s essential he never quits the chase, his cartoon-like tenacity, his willingness to pursue his prey to the ends of the Earth are crucial (hence a superb gag in Mission VI – the masterpiece of the entire series – when, as usual, he’s chasing someone and receives Benji’s phone instruction to jump out a window from a height, and he jumps), but so is self-inflicted pain: another law of Jackie Chan’s world – his body must suffer, must come into harsh contact with the world’s rough edges. Chan’s great films end with montages of outtakes showing real accidents, failed jumps, broken bones, and in Mission VI, Cruise clearly injures his ankle during a jump from one building to another. It’s practically written into his megastar contract that he must endure pain: we have to see him pay the price. In the old days, big stars like Cary Grant tried to hide the hard work; they pretended all they did was press a charm button. That was once the idea behind Bond, too: bodies are made for play. In recent Bond films, that’s no longer quite the case. And as for Cruise, the idea is we must never forget that he is, probably, the hardest-working star in the world.

Starting with Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (2015), the series was taken over by Christopher McQuarrie, a former successful screenwriter (The Usual Suspects) who, at a certain point, dedicated himself entirely to Tom Cruise as writer-director. (He directed him in Jack Reacher and four Mission instalments, and penned scripts for several others starring him, including Valkyrie, Jack Reacher: Never Go Back, Edge of Tomorrow, The Mummy, and Top Gun: Maverick.) The Mission: Impossible franchise thus enters a phase of fine-tuning but also of inflation – Mission V runs 131 minutes, Mission VI 148 minutes, Mission VII 163 minutes, and Mission VIII will be just shy of three hours. Cruise’s face, in turn, has started to look at times puffy and widened (who knows due to what treatments?), while his silhouette remains youthful, and his profile aquiline. His video message that served as the Super Bowl intro in February 2025 inspired all sorts of online comparisons with the latex masks he puts on in the films.

That being said, the three Mission instalments released so far under McQuarrie are very good. They are cleverly built on the legacy of the first four. By setting a sequence in Mission V – Rogue Nation during a performance of Turandot at the Vienna State Opera (with the Austrian Chancellor lounging in a box while assassins swarm backstage), McQuarrie not only shows appreciation for the legacy inherited from Brian De Palma but actually proves worthy of it. In fact, he goes even further back in film history than De Palma (and his far-off ’90s world, with Marcel Iureș inserting floppy disks into slots and genre films like this not usually stretching beyond an hour and forty-five minutes), by taking De Palma’s own model, Hitchcock, as a reference – Hitchcock, who masterfully played throughout his career (first in The Man Who Knew Too Much, 1934, then in the 1956 remake) with the idea of an assassination attempt at a philharmonic concert. Of course, this is a Hitchcock with a Hong Kong twist – the impossible missionaries perform kung fu moves and acrobatics on backstage rafters. But Hitchcock himself might not have minded – especially since Rebecca Ferguson spends the entire sequence in a splendid satin yellow one-shoulder dress with a thigh slit.

There’s a consensus that Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) – the sixth in the series – is the masterpiece. Among other merits, it finds Cruise an antagonist worthy of him: Henry Cavill (who had recently played Superman). Their relationship begins as a collegial rivalry; it ends with the two crashing helicopters into each other in the extremely narrow space between two rock walls. In the Superman films, Cavill had struck me as bland, but here – aided by a retro moustache, somewhat 1970s porn-star style – he is menacingly virile. And he has a great signature move: during a hand-to-hand fight, he shakes out his arms as if his fists were firearms needing to be reloaded. The film hits a first high point around the 30-minute mark, when little Cruise and massive Cavill team up in a dazzlingly pristine Parisian bathroom to immobilise a mysterious Asian gentleman (stuntman Liang Yang), only for the latter to wipe the floor with both of them for a minute and a half. (By the end, the bathroom – which had initially looked like a spaceship interior – looks like it’s been bombed.) Cavill fights in a tie, the suspect in a three-piece suit, and Cruise in just a blazer. The scene unfolds without music, only with sound effects, and it’s so cleanly choreographed and shot that we clearly understand both the differences in style between the three combatants and their differing levels – Cavill could beat Cruise, and the other guy could kill them both. Cruise earns extra points for his Hong Kong–style willingness to lose a fight on screen – even when he has an ally and the opponent is alone. And what’s even more remarkable is that Cruise and Cavill’s opponent is not a major villain, just a minor character – yet the film pauses while he throws them around. It’s a sequence worthy of the golden age of Hong Kong martial arts cinema.

Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (i.e. the seventh instalment, released in 2023; the one coming out this year is Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning) was received with equally positive reviews, but also with a fairly widespread, if only partially articulated, feeling that the high point of the series remained in 2018. Longer and more overloaded, with a title like a train that never finishes passing (though the film itself moves along quite smoothly), it didn’t earn quite as much money. And, as it faced the silence of less crowded cinemas, the PR drumbeat about Cruise’s real-life stunts, about how he’s the last bastion of authenticity, began to sound a bit desperate to some of us. Indeed, in an era when both the latest Indiana Jones and the latest Mad Max (Furiosa) are largely composed of heavily digitally manipulated or entirely computer-generated images – which at times make them look like animated films – the Mission: Impossible series really is the last stronghold. Cruise continues to fight for a kind of filmmaking where a crew goes out into the field, ventures into the real world, and – by investing fearlessness and broken bones – comes back with something that hadn’t been captured before. (“Captured” is the key word.)

The question is how much Cruise’s mission still matters to the wider public consuming spectacular imagery: how much does it matter where those images come from, how they were obtained, whether or not they carry a certificate of authenticity? As for his own camp – the “purists” – some of them might argue that Cruise’s work lacks the purity of Jackie Chan’s during his peak years. That’s what purists do, after all – they object to any impurity.

Seeing Chan around 1985, hanging over an abyss, meant believing him. Of course, there were all sorts of tricks even back then, but no matter how ingenious, they were still detectable to the trained eye. And there were camera angles that left little room for doubt that the abyss was real (and not a rear projection), and that Chan was Chan (not a stunt double), unstrapped and unwired. Cruise carries on Chan’s tradition under a new regime of imagery – one defined by virtually undetectable digital manipulation. You don’t actually have to see him hanging over an abyss anymore to really believe it. You also have to take his word for it. And even the promotional materials he puts out – about rejecting digital manipulation and insisting on doing for real what he appears to do on screen – admit that his refusal of digital tricks is ultimately relative: during filming, he was strapped in with cables that were later erased in post-production. He wasn’t crazy enough not to strap in, especially when the final result looks the same on screen.

Unlike him, Jackie Chan had no choice. The internet is full of debates about the CGI inserts in sequences like the HALO jump in Mission VI or the motorcycle cliff jump in Mission VII. It’s indisputable, someone says, that Tom Cruise jumped from a plane at very high altitude. Yes, replies someone else, but the storm he jumps into was created on a computer. It doesn’t matter, the first insists; the CGI was used to heighten the drama of the moment, without diluting or affecting the essence of the stunt in any way. Likewise, it’s indisputable, someone says, that Tom Cruise rode a motorcycle off a mountain trail with a parachute on his back. Yes, but in reality, he jumped off a specially built ramp, which was then digitally replaced with the treacherous path we see in the film. And why should that diminish the performance? It’s just something that makes the moment more dramatic.

I’m fully on the side of Cruise’s defenders: no matter what megalomania drives him, it’s petty to downplay his achievements. But the kind of cinema he makes can no longer be the cinema of Belmondo and Jackie Chan. In that sense, his is a fight that can’t be won.

Andrei Gorzo

Critic de film (n. 1978). Publică din 1996. Este conferențiar universitar la UNATC, unde predă din 2004. Filmul lui preferat este Al treilea om/ The Third Man(1949). Scrie pe andreigorzoblog.wordpress.com.