Interview with Radu Igazsag (part II): “People felt that something was going on in that film.”

“Footnotes” is a monthly column that aims to deconstruct the standard approach of the film history narrative, which is usually looked upon from only one direction, either straight forward or straight back. And it’s because there are many other things to notice around, careers, names, institutions, but also details omitted so far, some additions that still need to be made. The protagonists of these interviews are filmmakers who, for one reason or another, have not been active in the film industry for some time now, people whose memory I dig into to revive the dead time around chronologies. “Footnotes” is a column written by Calin Boto, the new member of the Films in Frame editorial board, which will come out on Tuesday, once a month.

It’s only the second interview, and the column has already partially betrayed its mission. It’s true that Radu Igazsag hasn’t directed anything else since his 2007 film (A Short Story), but his work is far from over. Not only does he have some works in-progress, but his activity has taken and continues to take many other forms. His pedagogical career, for example, which started in the ’90s and went through several institutions, including UNARTE (the Photo-Video Department), “Sapientia University” in Cluj-Napoca (Cinematography, Photography, Media), and UNATC (Multimedia and Animation). Or his involvement in the festival scene, since Mr. Igazsag has been collaborating with Animest, Super and Alter-Native for several years now. Moreover, it wouldn’t make sense to isolate his film work from his interests in visual arts, new media and photography.

My decision of contacting Mr. Igazsag was also influenced by this year’s edition of Animest, which dedicates a retrospective to Romanian animated film, marking its 100-year history. At the core of this retrospective is the film A Short Story, along with the latest book by film critic Dana Duma, The History of Romanian Animated Film. 1920-2020.The first part of the interview can be read here.

(Radu Igazsag presents the project of Wearing Off to Nichita Stanescu, a cinematic interpretation of the poem of the same name. The poet accepts.)

Radu Igazsag: But this whole thing happened sometime in the spring of ’83.

Calin Boto: So Nichita…

R.I .: We only saw each other a few more times, the last time was in November, he died on December 13th. It caught me by surprise. Sure, he had been in the hospital before and I knew he had cirrhosis, but he was only 51 years old. Plus, he was like a mountain, a strong, tall man. I had already announced at the studio that this project would be one of my proposals for the next year. Nichita said to me – “old man, there’s no way they won’t go with it, it’s not like the soldier is going to change, he’s been like this since forever!” So we went with our proposal, but we got this answer from The House of the Free Press (i.e. – the former Casa Scânteii) – “we shall see, let’s wait for a bit, let’s not hurry, let’s not exploit the fact that he just died, perhaps it was better to think of a film that could be like a tribute to the poet … ” But that’s what I actually intended to do, begin with some lyrics, but unfortunately they don’t appear in the film, because that was their first condition. I had agreed with Nichita – “okay, old man, so be it!” – to use four verses from a very beautiful poem of his, A Poet, Like a Soldier: “A poet, like a soldier / has no life of his own. / His own life is wrecks / and ruins.” That’s how the film was supposed to start, with these lyrics by Nichita Stanescu.

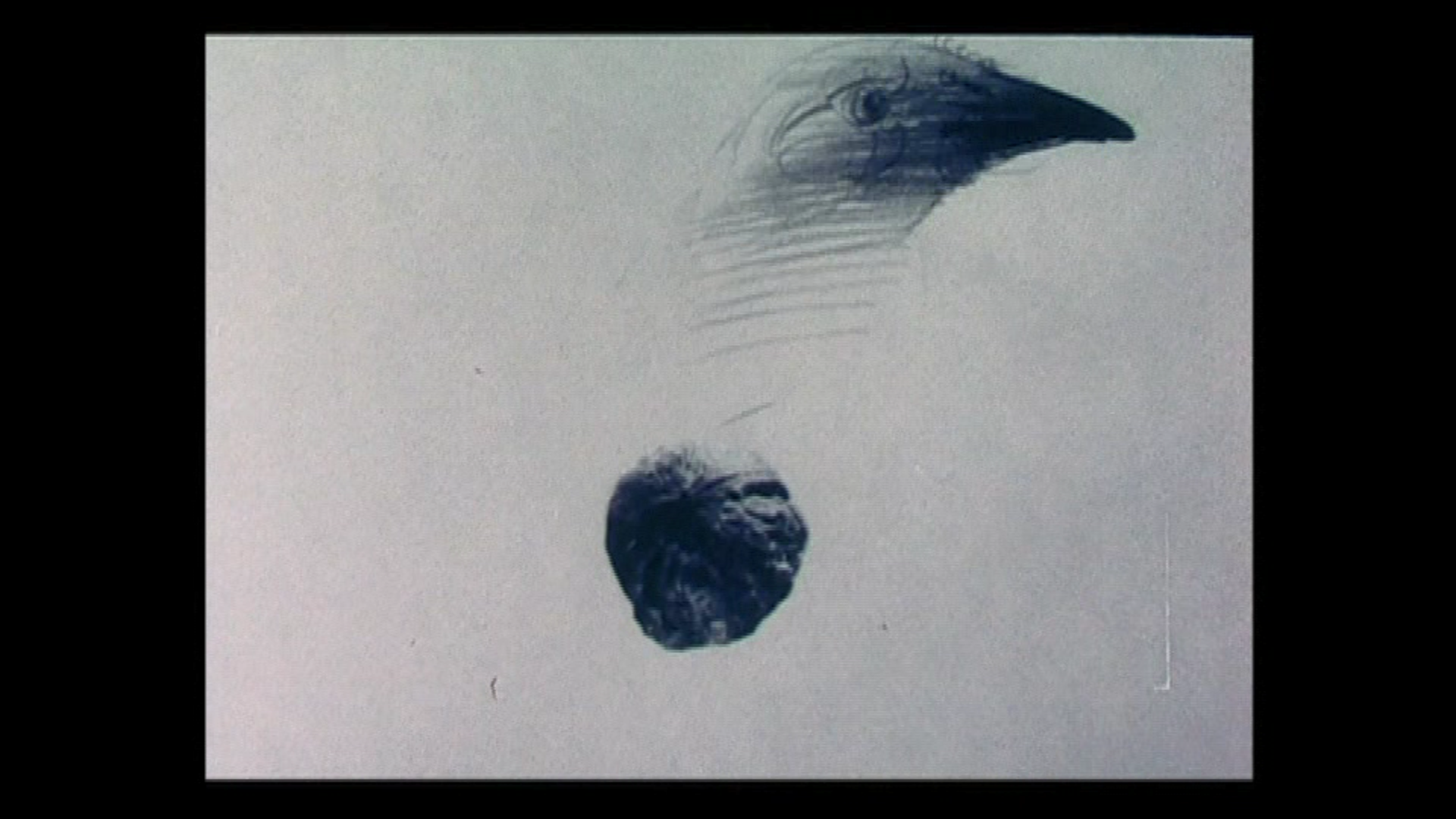

When the project was under review in the fall of ’83, and Nichita had died in the meantime, the answer was that these lyrics don’t help the film at all, that it’s better to take them out and put the project on hold, while I focus on other films. Two more years passed and it wasn’t until ’85 that I got the approval to make it. The découpage remained just about the same, with minor changes. The four verses should have appeared before the title, and the film should have started with “The soldier was marching”. And then we should have seen one soldier emerging from a sea of soldiers. Now that Nichita was dead, it was even clearer to me – if we can’t put those verses at the beginning of the film, then we have to somehow enter the world of that soldier we’re getting closer to, and that is obviously Nichita. I went to his mother, in Ploiesti, and I told her and Nichita’s sister that the film can finally be made and that I would like to show through photos memories of his home. That’s what soldiers do, as I remember – when there’s nothing else to do, the soldier is thinking of home, far away from the army. I wanted to revive his world a bit, all the things in the film are real, they’re from his house, from the room where he was born, including the face of Dora, his second wife. The only thing I couldn’t have anymore was his hands on the piano, so I asked a pianist instead, and in the film his hands are blurred. We wanted to enter his world, so that after we can see how the soldier is wearing off, and at the end we’re left with Nichita’s portrait. Then the sky is turning dark and you get trampled by a different soldier, then another one and so on, and in this scene I wanted to include the complete poem, which is short, only one minute long. I didn’t want to add the verses that were refused before, when I made the copy in the ’90s, it felt immoral to me. I finished the film in ’85, and then years of discussions with comrade (Mihai) Dulea, deputy minister of culture (vice-president of the Council of Socialist Culture and Education) followed. The discussions started at Animafilm, then at Casa Scânteii, and so on until they reached comrade (Suzana) Gâdea (president of CCES). I knew from other similar situations that they might ask to cut a scene, a sequence, a line, something or, on the contrary, to add something else, and that way the problem was solved. Here they were stalling, they weren’t giving me any instructions. I remember that in one of the four meetings I had with Dulea – long and usually in private, at one point he asked me: “Comrade Igazsag, what can the viewers make out of this film? Those red geraniums in the window, what’s up with them?” I took the picture at the window of Nichita’s room, which had a white curtain. Green leaves, red flowers, white curtain … “You should know that I also speak Hungarian”, he told me. And other such nonsense. That it’s not very clear who are these soldiers, that they thought it would be about NATO soldiers, invaders … Anyway, once or twice a year I would meet with such a character.

C.B .: So the film was not actually banned, but rather suspended.

R.I .: Yes, it didn’t follow its course, didn’t reach its finale. Although a copy has been made. At one point I was with Dulea and Marin Stanciu, the head of Romaniafilm, and when we left, Stanciu came with an idea – to run to Animafilm and ask the director for a car to go to Buftea, and to take the negative there (I kept it at home because some idiots wanted to throw it away). During this time, he would call at the editing lab in Buftea and arrange for them to make me a copy using the negative and the sound mix. I still have that copy in my closet. But the real copy, with corrections, was made in January ’90. It was shown in festivals and so on. That was its little story, though it wasn’t a film that would have, God forbid, harmed the government or something like that. I’m sorry Nichita only caught the project, after that I had to make the decisions myself. I had the chance to talk to him about the music in film. He was a great connoisseur and lover of music, he played the piano very well, among other things. I chose one of the pieces I had agreed on with him, the Funeral March from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, but we only agreed on it as an option, not as the final choice.

Now it’s easier to talk about it, but the whole thing was very unpleasant at the time. For several years I could only work on series. Funny thing is that in the fall of ’89 they gave me the green line for another project, The Nut and the Wall (1991). A lot of projects remained unfinished, but fortunately I managed to make the films in the few years after the Revolution, when Animafilm was still doing well: ’90, ’91, even ’92 … And One Day (1991) was an early project, I wanted to make it in the mid-1980s; it followed a day in the life of a soldier, and was based on my life. They found the original title a bit inappropriate, The Last Day of an Unknown Soldier’s Life. “What’s with this title, what do I mean by that?” Unfortunately, it got pretty hard to make films after the ’90s. At Animafilm, things dissolved in just a few years. For example, I managed to make At a Barrier and the Bobor in 2004, which I presented to the studio in 1984. It took twenty years! But, at least, I got to make other films. Making animation was more complicated under these new circumstances, film stock was more and more expensive, the acetophenone, all these things …

Since I didn’t want to move on from this episode just yet, I brought up the role of photos in Wearing Off and Family Snapshots.

“I took photography more seriously, so to speak, when I was a student at Painting. But the approach to a hand-made image in a realistic key, I had it since high school. That’s when I found out about the hyperrealism in the West. Sure, realism was known even before romanticism, and it kept evolving, but then appeared a whole new dimension of realism in visual art. I had teachers who understood this criss-cross between arts. They encouraged us to experiment with that. Plus, these two films also have a side of documentary, you can see the intention. Like I said, I wanted that soldier to be Nichita himself, and the story in Family Snapshots is inspired by my own family. And one more thing – when I started this film in the spring of ’83, we got some awful, shocking news, that my father had cancer and only half a year to live. He didn’t even get to see the film. Those are the actual faces of my father and my mother. His disappearance in the film is based on his disappearance from our family. I thought it would feel more natural and real if the elements are from the world I’m making the film about. But it’s also animated. I remember that in ’84 we had a huge exhibition on Romanian animation at the Dalles Hall. Today something like that is hard to imagine. Each of us prepared their own materials, we thought about how to exhibit them, we had stills from films, the making-of, so to speak. There I exhibited some drawings from Family Snapshots. Comrade Dulea saw them and told me that I was a very good photographer. Even colleagues at Animafilm thought they were photos. Of course, this realistic bet is quite important when you want it, when you need such an image. I remember Zoltán Szilágyi from college, when there was a competition on hyperrealism between colleagues, and one friend said, “it’s like you can reach out and grab the object from inside”. Such an invasion of the real world in film, whatever you make, is inevitable when you work, but also when the subject allows it. During making Wearing Off, I kept telling myself that Nichita should have been there to agree to what I was doing. He was a judge from beyond. I could have dropped both projects, but when something like that happens, then the responsibility falls on the survivor. I remember when I finished Family Snapshots in early October ’83, my father had died in September, so I invited my colleagues who wanted to see the film. It was a tradition at Animafilm. I didn’t need to talk about my father’s death, the team already knew about it. After the screening, some colleagues told me they cried during the film. I didn’t want to make a tear-jerking film, but I had similar reactions from people who saw it in the cinema. Even though they didn’t know about the real event, people felt that something was going on in that film.”

A small disturbance of our ambiance, caused by some unexpected events. A walnut falls on the ground between me and Mr. Igazsag, more than likely dropped by one of the crows that is struggling to find a spot on the few trees left on the boulevards of Bucharest. It was nothing, after all, but I couldn’t help but shudder almost childishly and remember that the same thing happens in The Nut and the Wall.

“As I was saying, I started a collaboration with the Visual Arts Foundation (FAV), I made films which had a fair share of animation, Ciacona (1994), At a Barrier and the Bobor, and even A Short Story. Apart from that, the Romanian Television didn’t want to take risks with such works, although they kept saying “let’s do it, let’s do it”, but all the projects fell apart. Other studios didn’t dare either, the stakes were far too low. A ten-minute film, what can be done with that? For years, the Romanian Film Center (CNC) didn’t have a special category designed for animation, there was only one category for all of them, short and feature film, animation and documentary. Finally, now there is a special fund, films are being made, everything is, let’s say, normal.”

C.B .: Let’s go through them chronologically. In 1990 you founded the Photo-Video section.

R.I .: I remember it was the spring of 1990. Mircea Spataru, an extraordinary artist I knew from Cluj, was appointed the new rector of the Arts University. I was still at Animafilm, I had just finished The Nut and the Wall and I think I had started working on One Day, so I was working nonstop. He called me. Until then, they would teach photography only at Design, which one might see as being closer to the graphics used in advertising and printing. He asked me if adding video art to the curriculum seemed like a good idea, since it was quite popular at the time. We filed a petition to the ministry. I think the first admission to the Photo-Video section happened in ’93. For start, we went with an optional course, open to all departments. The first one was on photography, because it was easier for us technically speaking, both me and Iosif (Király) had our own cameras. The following year we added a course on video art as well, since many artists had started to be interested. The first years we worked with our own cameras, the school didn’t have any. Obviously, VHS for amateurs. Luckily, Alecu (i.e. – documentary director and cinematographer Alexandru Solomon) and I could work with two beta cameras at FAV, which was the best one you could have at the time, and with the permission of DoP Vivi Dragan Vasile we could also borrow them for our classes at the University. I met Alecu Solomon in 1986. He finished “Tonitza” High School of Arts and didn’t get in at Fine Arts, so he got hired at Animafilm. He was assigned to my team by a production manager. I helped him prepare for his admission to Cinematography, where he entered (class of 1991), and after FAV was founded we collaborated on many films, documentaries, experimental, hybrids. Finally, I could do things that I couldn’t even dream of before.

In parallel, I also dealt with the Multimedia project of the Film section within ATF (i.e. – Academy of Theater and Film, currently UNATC – National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale” in Bucharest). Horea Murgu told me at one point, I think it was 1991, that an editing and sound section was needed, because at that time they only had Cinematography, Directing, for both theater and film, and theoretical studies, for Theater-Film, as well. We put in a request, Victor Rebengiuc was rector and Stere Gulea was dean at the time, both of them supported us, and the project proposed two years of joint study and one that offered three directions as majors – Editing, Sound and Animation. For ten years, maybe even more, I taught at both Universities – UNARTE and UNATC, and I also made films at FAV, so there was a lot to juggle. I was glad to see that it only took a few years for photo-video sections to be created in Cluj and Iasi, too. By the end of the ’90s, it was quite clear that we were going towards the digital age, I remember that in 1996 we bought our first digital camera at ATF, it was like a soap dish, but it cost us, I don’t know, like $1360, quite a lot. We all loved shooting on film stock, but once this new technology was on the market, you wanted to try it, even if it meant using those cheap devices. Cheap meaning simple, because they weren’t cheap at all. I remember buying a memory card for the camera, the largest at the time – 256 Mb. Then the computer appeared.

Since Mr. Igazsag played, as he says, a key role in anchoring artistic studies in the new media, I asked him to talk about another of his preoccupations in the ’90s, more precisely recovering the Romanian avant-garde and neo-avant-garde through exhibitions and catalogs. Not because the two activities would have defined him 50/50, but because they are two opposite but complementary directions for creating a scene – fast forward to the past, fast forward to the future.

“There was a large exhibition at the National Theater, Experiment ’60-’90 (curated by Alexandra Titu, 1996), organized by a large team which I was part of, as well. In the process we managed to recover works made as early as the 60’s, so during our lifetime, only that large part of the artists had died or left the country, we couldn’t find their works anymore, the documentation was insane. We were even contacting aunts of the fugitives in our effort to find their sketches, pure madness. There weren’t a lot of works in the video art area, but there had been an interesting movement that included Ion Grigorescu, with films on 16 and especially 8mm. They were first brought to light in the ’90s, we used to see them in our studios before. It was important to show the world that these things happened, just as it was important to realize that if the world didn’t pay a lot of attention, then much of it would have been lost. Because they can easily disappear. During the Revolution, for example, all the sculptures by Ovidiu Maitec burned at the artists’ studios near the Romanian Television headquarter. A terrible blow, exactly what happened to (Theodor) Pallady during the bombings in ’44. A whole wave of discoveries came with the exhibition, including memoirs, books that were kept out of sight. Let’s not forget that there were intellectuals who hadn’t even heard of Corneliu Coposu before ’89, just as they hadn’t heard of many other writers that hadn’t been published in their time. We even had this discussion when we were preparing the catalog for the exhibition, we were concerned that no one would believe that we couldn’t come with an exact date of creation for a work made in the ’70s. After all, we’re not talking about the seventeenth century, but only a few decades ago. Also, we didn’t have photos or videos of the performances, so we took testimonies – that it happened at night, on a hill, there were candles … It’s very unpleasant to have a recent history and no documents to attest for it. Especially when it comes to these events, these happenings, and if they haven’t been properly documented through photographic, video, or audio-video materials … Okay, we’re not talking about the cases where the artists refused such recordings, even Sergiu Celibidache didn’t want to be recorded. But when there are testimonies, clear data, things are beyond doubt. Even a more delicate, fragile field, such as art, needs clear, credible, dated testimonies. We were surprised to find out that there were authors who didn’t remember the dates of their works. Sometime in the 60’s … One of the things that UNARTE and UNATC students and graduates realized is that it’s imperial to sign and date your work. Until historians come to research it, it’s the artist’s job to do it. Well, today is not a problem anymore, people are used to doing that.”

C.B .: Is A Short Story your last film?

R.I .: No, I still have some films in the works, about three. It’s getting more and more complicated to complete a film these days. I always had other activities as well, like painting, drawing, engraving. After all, it’s normal, I learned all these crafts and I express myself however I can. Not everyday you have the proper conditions to make a film, but I can always find a sheet of paper and a pencil. In the last ten years, I’ve been very busy with this UNATC animation thing. We decided to set up an Animation section for the high school students, because we had already had a master’s degree for about 20 years. We had our first admission process in 2016, but our proposal had been in stand-by for about ten years at the ministry. Some people have to invest a lot of time, patience and many more. Institutions are administrative-financial entities and what have you, but this thing has to be filled with students, on the one hand, and then with some teachers, otherwise it doesn’t work.

Film curator, writer and editor, member of the selection committees of BIEFF and Woche der Kritik, FIPRESCI member and alumnus of the film criticism workshops organized by the Sarajevo, Warsaw and Locarno film festivals. Teaches a course on film criticism and analysis at UNATC. He has curated programs for Cinemateca Română, Short Waves, V-F-X Ljubljana, Trieste Film Festival, as well as the Bucharest retrospective of Il Cinema Ritrovato on Tour in 2024 and 2025.