Depp vs. Heard: between cyberpolitics and cyberbullying, commercialization and social media surveillance

My aim with this article is to emphasize that the history of politicizing violence against women is older than the #MeToo movement, that in the public discourse surrounding the Heard v. Depp trial there was an attempt to co-opt the movement and delegitimize a collective narrative that highlighted how widespread harassment is, and that we should reflect carefully on the link between the commercialization of violence and social media surveillance. What I won’t do is dispense justice from the keyboard and it’s only fair to mention that from the beginning; I won’t comment on the case, the evidence, the testimonies, the messages, nor will I explain the defamation trial.

Acknowledgment

Violence against women has been and continues to be strongly linked to acknowledgment.

We are therefore talking about an acknowledgment process that has not ended, that has seemed to accelerate at certain key moments or that may face regression. The feminist movement has put violence against women on the public and political agenda, brought it to light, and characterized it as a violation of human rights and a form of gender-based violence. The autonomous feminist movements have made the most important contribution to the adoption of progressive public policies in the field of preventing and combating violence against women. Laurel Weldon and Mala Htun (2013) showed in the article “Feminist mobilization and progressive policy change: why governments take action to combat violence against women” that feminist activism was the determining factor in policy change in 70 countries, between 1975 and 2005 [1]. When it comes to regressive interventions, the factors can range from illiberal movements against gender equality to lawmakers who amplify the process of de-democratization through their interventions that limit access to rights and freedoms. An example might be the backlash against the Istanbul Convention and the later withdrawal of some of the signatory countries, such as Turkey and Poland, or the refusal to ratify this document, as Bulgaria did, under the influence of the Orthodox Church, to give just one example. Public discourse and perceptions of violence lie somewhere between progress and regression, to use a common distinction. Traditional media and the development and expansion of social platforms are components of the discussion on the acknowledgment of gender-based violence. It is impossible to avoid the media in this conversation given that it can contribute greatly to the visibility of the phenomenon, can give legitimacy to victims or survivors or can reduce them to silence, can trivialize violence, can build stereotypical representations, can provide information and reveal abuses kept quiet because it takes context, momentum, for the victims to speak out. We’ve known this for years, #MeToo only reminded us.

An older history: knowledge

Violence against women is not only about acknowledgment but also about knowledge.

The discussion about violence against women goes further back than 2022, and it has an older history than #MeToo. Therefore, we have a broader and more complex context than the Heard v. Depp case. This history tells us that we cannot draw conclusions from a one-off drama and turn them into principles, be it the drama of some famous actors that we may like or despise, one that we have seen unfold in the public space. The status of active viewer, intensified by the online environment, does not legitimize any conclusion elevated into principle, such as “women lie”, “women abuse men”, “the justice system doesn’t do justice to victims” or “abusers get away with it” or “you can’t trust the justice system”. Or “#Metoo was a fake, #MeToo died”. I have listed only a few of the ideas that were articulated and circulated in the public sphere after the verdict. I believe that we need minimal knowledge of the history of politicization and validation of violence against women – which, in fact, comprises many local or regional histories – in order not to fall into the trap of investing a life story with great symbolic meaning.

In the 1970s, the feminist movement began to criticize more and more assertively the unequal power relations between women and men, traditional gender roles and behaviors. This women’s liberation movement re-examined the status quo of gender relations in society, and violence against women became a central theme in the dynamics of this mobilization. A number of female authors, researchers and activists have revolutionized the thinking, community organization and policies on violence against women.

The fight against violence against women was central in the 1960s and 1970s, in the second wave of feminism, in women’s liberation groups in the United States, Europe, and other Western democracies. The practical agenda of this wave of feminism, of radical feminism essentially, included centers of crisis, freedom of movement and safety in the public space. The thinking and activism of this period have contributed greatly to shaping a feminist political approach to violence against women [2]. Of course, I can’t sum up this rich and complex history in just a few pages, but what I will do is affirm once again that it exists. The discursive architecture, networks of key players, interaction with politics and public policy development, media representations of this phenomenon, the role of the United Nations, the dynamics between states and the European Union or other structures in this space, such as the Council of Europe, should we look at any given geographical area, they are all substantial and can be analyzed on several levels, from local to cross-border scale. Violence against women was considered a matter outside politics [3]. It’s a private matter, why should politics get involved in what happens in people’s homes? Because. Otherwise, justice ends at your doorstep, as Susan Moller Okin said. The principles of justice should apply to the private, domestic sphere as well. Violence must be acknowledged as violence whether it takes place at home, outside it, at work, or in politics if we get to the present day.

The link between male domination and violence was observed and called into question by feminist thinking and action, researched by female authors in scientific fields such as women’s studies, feminist studies, and gender studies. And this research on unequal power relations between genders has contributed to the substantiation and development of public policies.

Violence against women has gradually gained international recognition. But we still have a long way to go. Events that seem to be almost cyclical remind us of the discrepancy between measures and reality, between the acknowledgment of abuse and victim-shaming, the latter sometimes seems to sum it up perfectly. I’m inclined to believe that the likes of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, Donald Trump, Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby have this role to show us, again and again, this discrepancy, which is essentially due to public reception.

Beyond the silence: power

Feminist movements have contributed to building a collective political narrative, a collective awareness that violence exists but is hidden behind closed doors or masked by sunglasses and makeup. Women have begun to understand that it is not a shame, more importantly, it is not their shame, that it is a common experience for many. So they began to break the silence. This process of breaking the silence is far from over.

Still, there is a difference between the public treatment of women and their rights today compared to how it was 50-60 years ago. As there is a visible democratic regression in Europe, the United States, and Latin America. This democratic regression is also amplified by campaigns against gender equality, politicians of the populist, far-right, religious institutions, and non-civil society organizations (Băluță, O, 2020; Băluță I, 2020; Norocel, Băluță, 2021, and others).

In this process of re-signification and re-conceptualization of violence against women, we also notice a shift in the power dynamics due to the fact that women have become agents of change and have transformed an experience perceived as personal and private into a political one. They called for the acknowledgment of violence as a violation of women’s rights, as a form of gender inequality, and for specific public policies. These changes didn’t happen overnight, but slowly.

When you don’t acknowledge the victims, when you don’t admit that there is violence, when you delegitimize the people and the acts themselves, you actually restore this imbalance of power. You re-establish that men most often have power over women, that abusers have power over victims, that state institutions have power over women, you restore relations of domination and control.

#MeToo and symbols

#MeToo is yet another proof of the universality of violence. The hashtag helps us look at violence, paradoxically, beyond the individual, it shows a collectivity of common experiences, shared mostly by women.

Tarana Burke is the activist who started the MeToo movement in 2006, aiming to raise awareness about sexual violence. She named it as such to promote solidarity, especially with black women, who are usually marginalized. In 2017, the hashtag MeToo was posted on Twitter by actress Alyssa Milano, shortly after The New York Times article was published. Journalists also played an important role in creating this space where victims of abuse could speak out. On October 5, 2017, The New York Times publishes an investigation by journalists Jody Kantor and Megan Twohey. On October 10, 2017, journalist Ronan Farrow publishes another material in The New Yorker. Reporters investigated for months and managed to expose film producer Harvey Weinstein’s 30-year span of abuse and sexual assault. In 2017, Time magazine awards the title of “Person of the Year” to those who broke the silence, The Silence Breakers of #Metoo. In 2018, the journalists who investigated and wrote about the sexual abuses are awarded the Pulitzer Prize. These are just a few examples of #MeToo being acknowledged and gaining visibility, without getting into what the movement meant for victims of sexual assault. But it also got some backlash at the time. And the Amber Heard v. Johnny Depp trial refueled this backlash. To some extent, “Haters gonna hate and potatoes gonna potate” with or without Heard v. Depp.

Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein…

I should write it 30 times. One for every year he has sexually abused women. In 2020, the former producer was sentenced to 23 years in prison for rape and sexual assault. A case also considered representative for the #MeToo movement. Although it’s recent history, we forget. And Amber Heard v. Johnny Depp is another story that took place on a well-worn path.

Looking beyond the celebrity world, what do we do with all the women who have faced violence? How do we ensure that a defamation lawsuit does not become a PR strategy for abusers? Women in Hollywood can also face violence, sure, just as violence against women must not be reduced to the celebrity life and culture.

Diana, Maria, Carminda, Jane, Eleonor, Krassimira, Albertina, Hiroko, Indira… A lot of “nameless” women, who do not carry the burden or have the privilege of notoriety to draw the media’s and the public’s attention. They, too, are part of #MeToo. Maybe it’s job-related, but I stay away from heroes and symbols, personalization and mythization. Media, generically speaking, builds heroes, turns them into symbols, creates myths. If we take a step back and take a deep breath, we notice that during the few weeks of trial and insistent glances thrown through the keyhole another process has begun, one of co-opting the movement. And co-optation also means simplification. If Amber wins, then #MeToo wins. If Johnny wins, then #MeToo loses. Just like when we were children and plucking the petals from a flower: he loves me, he loves me not. Simplification and personalization are of no use to anyone. Tarana Burke noticed the co-optation and manipulation of #MeToo during the trial and said that we are living “(…) one of the biggest defamations the movement has suffered.” The proclamation of #MeToo’s death is an over-interpretation and shows a far-fetched attribution of symbolic meaning.

No wonder well-intentioned activists and researchers feared the possible negative effects on victims or survivors. But let’s also ask ourselves why this is happening, let’s look critically at this process of personalizing a collective movement and narrative. Attributing a radical/revolutionary symbolic meaning to this process of personalizing the movement or to the toxic relationship between the two actors or to a decision taken by the justice system, it’s all just a trap. The #MeToo movement has focused on social systems that perpetuate gender domination and inequality rather than on individual cases, and the systemic approach is one of the pillars of the mobilization. During the movement, women, victims of violence, demanded to be heard and drew attention to the fact that they face systemic gender discrimination. Similar stories and experiences shared by women have created a collective narrative that has shown how widespread sexual harassment is. Millions of survivors, not only in the United States but around the world, have used social media to talk about violence.

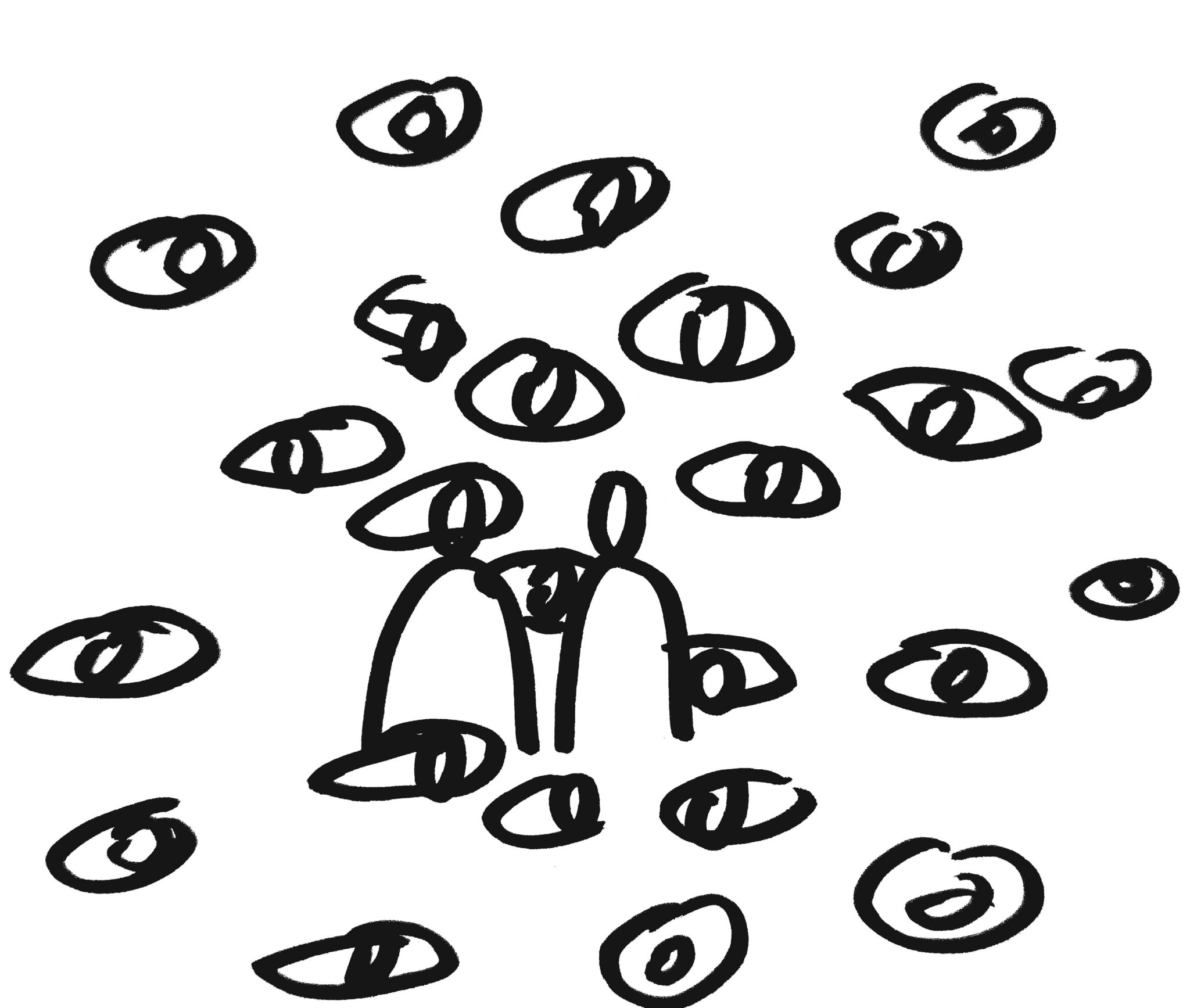

Social media & digital surveillance

But, as studies show, digital technologies are a platform where different political interests come into conflict and fight for influence. Not all interests are liberal or democratic (Tucker et al. 2017, 48). The Court of Public Opinion may establish that a woman is lying even before the actual trial begins or the verdict is pronounced. Also in the Court of Public Opinion, we see a cultural response to gender-based violence where people resort to discrediting and harassment. The brutal reactions toward Amber Heard have their roots in the socio-cultural making of gender, gender roles and normative behaviors, in the perception or expectation of the “perfect victim”. Public discrediting and tactics aimed at delegitimizing those who talk about violence didn’t appear now with this process. The right to a fair trial is one of the foundations of our societies, I don’t mean that women always tell the truth or that men are always guilty [4]. I think you can criticize or confess your doubts about someone being a victim of violence without acting as an executioner. I don’t like executioners in the public space who make use of every tool digital technologies have to offer precisely because they feed a climate that instigates hatred, contempt and sexism. Executioners in the public space contribute to expanding the culture of silence, the very one #MeToo has criticized head-on.

The viralization of memes reflecting cruelty or of acid comments on social media reveals the tastes and representations of an audience that resonates with patriarchal representations. Heard v. Depp shows us once again how domestic life is transformed into data and entertainment, how individuals’ privacy can be diminished and how social media surveillance is on the rise. I think there is something profoundly wrong when the commercialization of violence overlaps with digital surveillance, and individuals and executioners give verdicts as simply spectators. I think it is sinister for the democratic system, for a projection of democracy where the principles of justice do matter, nonetheless.

Lecturer at the Journalism University of Bucharest and associate professor at Political Sciences University. And an earnest activist for women rights.